Quincy History

The site of Quincy, Illinois, originally was home to Sauk (Sac), Fox and Kickapoo Native American tribes.

French-Canadian explorers, fur traders and military mail carriers later traveled the Mississippi River, passing the bluff on which Quincy would be built.

Quincy’s founder, John Wood, came west from Moravia, New York in 1818 and settled in the Illinois Tract, the area between the Illinois and

Mississippi Rivers which was set aside by Congress for veterans of the War of 1812. In 1812, Wood purchased 160 acres from a veteran for $60 and the

next year became the first settler in what was originally called “Bluffs,” and by 1825 would be known as Quincy. John Wood was impressed

with the location’s timber, fertile soil, abundance of game, and especially by the fact that it was the only site within 100 miles where the bluff reached the Mississippi River, which also

had a natural harbor. Wood was later elected Lieutenant Governor of Illinois in 1856 and became Governor in 1860 upon the death of elected Governor

Bissell.

In 1825 the state of Illinois sent commissioners to the newly created County of Adams to locate a county seat. The commissioners drove a stake into the public square (John’s Square) and named the settlement Quincy in honor of the newly-elected U.S. President, John

Quincy Adams. John’s Square became known as Washington Park in 1857 and was the site of Quincy’s Lincoln-Douglas debate the following

year.

The mid-1830’s was a time of rapid growth for the new community. The establishment of the Quincy Land

Office brought individuals and families desirous of purchasing land in the Illinois Military Tract. Once here, many decided to remain in

Quincy.

Five thousand members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, the Mormons, were driven from their homes in Missouri and arrived in

Quincy during the winter of 1838-1839. Though vastly outnumbered by the new arrivals, the residents of Quincy provided food and shelter for the

Mormons until Joseph Smith led his followers 40 miles up river to the settlement of Nauvoo.

Quincy’s earliest settlers, primarily from New England in origin, were joined by a wave of German immigrants in the 1840’s. The new residents brought with them much needed skills for the expanding community. Saw mills flourished as the rich

forests of walnut, oak and hickory were cleared for building and farming, and crops grew in the fertile soil. Flour mills and pork packing plants

shipped their products from Quincy’s growing riverfront. German, and later Irish populations, each grew in size, enabling them to form their own

churches.

The matter of slavery was a major religious and social issue in Quincy’s early years. The Illinois

city’s location, separated only by the Mississippi River from the slave state of Missouri, made Quincy a hotbed of political controversy.

Sixty-five community leaders chartered the Adams County Anti-Slavery Society, the first in Illinois.

Dr. Eells House, at 415 Jersey, was considered station number one on the Underground Railroad from Quincy to Chicago. Dr. David Nelson’s Mission Institute, an abolitionist training school, was also on the Underground Railroad.

In 1841, three abolitionists with the Mission Institute, Alanson Work, James Burr and George Thompson, were apprehended while attempting to entice

slaves away from their Missouri masters. They were sentenced to 12 years each in the Missouri Penitentiary. Thompson’s Prison Life and Reflections focused national attention on the anti-slavery cause in general and Quincy’s role in particular. In 1842, one of Quincy’s earliest physicians, Dr. Richard Wells, was convicted of aiding a fugitive slave, and was fined $400 by local judge Stephen

Douglas. Although quite a large sum for the times, it turned out to be a paltry one compared to the thousands of dollars Dr. Eells spent taking his

case to the State and Federal Supreme Courts. Although he died before his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, his attorneys, including two members of

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet, William Seward and Salmon Chase, carried this important case through to the end.

Quincy grew rapidly in the 1850’s. With a population of 13,000, it had become Illinois’ third

largest city. In 1853, the U.S. Congress designated Quincy a port of entry for foreign goods. Three years

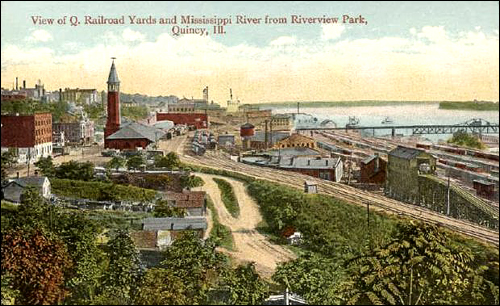

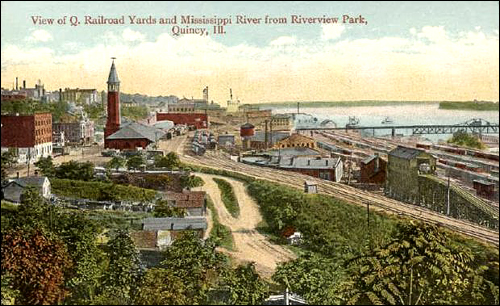

later, nearly 3,000 steamboat arrivals and departures made Quincy’s riverfront a beehive of activity. A railroad link to Chicago and the East

Coast brought immigrants and facilitated the movement of Quincy’s products, including grain, stoves, wagons, furniture and later pumps and compressors. Underlining Quincy’s statewide importance, the city was chosen as a site of one of the seven Senatorial debates by U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas and his

challenger Abraham Lincoln. Quincy was the largest city in which Lincoln and Douglas appeared and its citizens recognized the national significance

attached to the event. More than 12,000 people stood, filling Washington Park and the streets around it to hear the debate. Although Lincoln lost his bid for the Senate seat, the debates made him a national figure. In a December 1858

meeting of Horace Greenley and Lincoln’s Quincy friends in the Quincy House at 4th & Maine Streets, Lincoln was first publicly mentioned as a possible Presidential

nominee.

The Civil War brought increasing prosperity to Quincy. Wartime food needs ensured a strong demand for

agricultural products and government orders for clothing, saddles and harnesses stimulated production in those industries. Quincy’s founder,

John Wood, served as Illinois’ Governor in 1860 and was Quartermaster General for Illinois during the war. Quincyans Orville H. Browning and

William A. Richardson represented Illinois in the U.S. Senate and Browning later served as President Andrew Johnson’s Secretary of the Interior.

In 1870, Quincy passed Peoria to become the second largest city in Illinois with 24,000 residents. A

massive railroad bridge across the Mississippi River had been completed, and Quincy was linked by rail to Omaha, Kansas City and points west.

Substantial brick homes lined Quincy’s streets and the community saw limitless opportunity ahead.

Mark Twain recorded his observations of Quincy in 1882. “In the beginning Quincy had the aspect and

ways of a model New England town, and these she has yet; broad clean streets, trim neat dwellings and lawns, fine mansions, stately blocks of commercial buildings and there are ample fairgrounds,

a well-kept park and many attractive drives; library, reading rooms, a couple of colleges, some handsome and costly churches and a grand courthouse, with grounds which occupy a

square. There are some large factories here. Manufacturing, of many sorts, is done on a great

scale.”

A number of Quincyans have achieved fame over the years. These include political figures such as U.S.

Senators Stephen A. Douglas, Orville H. Browning, William A. Richardson, Illinois Governors Thomas Carlin, Thomas Ford and John Wood; novelist Katherine Holland Brown; songwriter Henry Clay Work;

America’s first African-American Catholic Priest, the Reverend Augustine Tolton; actors Mary Astor, Fred McMurray and John Anderson; artists John Quidor and Neysa McMein; and inventor Elmer

Wavering. Confederate General George E. Pickett studied law in Quincy with his uncle attorney Andrew Johnson. While here, Pickett was active, along with other young Quincy men, in a dramatic club that produced plays in a theater on Third Street between Maine and

Hampshire Streets. As ladies did not appear on 1840’s stages, George Pickett portrayed female roles in the local productions.

A Quincyan prominent in the transportation field was Thomas Baldwin. A pioneer in the development of the

hot air balloon and the parachute, Baldwin jumped from his balloon, “City of Quincy”, and parachuted safely into Singleton Park at 30th and Maine Streets on Independence

Day in 1887.

Although his jump in Quincy was only his second, he quickly gained national fame and was sought by the county’s amusement parks. Following two worldwide tours, Baldwin returned to Quincy and purchased Singleton Park. The park contained an

amphitheater, a one-mile racetrack with a grandstand, a baseball diamond, a clubhouse and even a saloon. When public interest waned in Baldwin’s

parachute jumping, he started balloon racing. In 1908, he was commissioned by the United States Government to build its first dirigible. Thomas Baldwin is honored at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Quincy’s municipal airport appropriately commemorates Baldwin’s accomplishments in its name, Baldwin Field.

As Quincy began to shape its second century, neighborhoods once connected by streetcar lines gave way to suburban housing as the city’s

boundaries spread eastward. Not lost, however, are Quincy’s tree-lined streets and architectural treasures which give the city the largest

variety of significant architecture in Illinois outside Chicago. Quincy’s East End, Downtown and South Side German National Register of Historic

Districts are a reminder of the past and a promise of the future. For more than a century and a half, Quincy has counted its blessings and good

fortunes, endured an occasional flood or tornado, and settled in as the Gem City of the Mississippi Valley. Twice recognized as an All-American City,

Quincy honors its past as its citizens look forward to the 21st Century.

USE YOUR BROWSER'S BACK BUTTON TO RETURN :